<1>Defying the oft-refuted yet persistent notion of

Victorian separate spheres, the nineteenth-century woman understood

the double burden of home and work. Florence Nightingale writes in Cassandra

(1852) of the typical woman that “If she has a knife and fork in her

hands during three hours of the day, she cannot have a pencil or

brush” (30). Frances Power Cobbe echoes the sentiment a decade

later: “No great books have been written or works achieved by women

while their children were around them in infancy. No woman can lead

the two lives at the same time” (“What” 598). And Mona Caird is

still lamenting the challenge at the end of the century when she

writes, “To man, the gods give both sides of the apple of life; a

woman is sometimes permitted the choice of the

halves;–either, but not both” (171, emphasis mine). Pencil or fork,

books or children, one side or the other: according to the

narrative, women are permitted a choice of marriage or work.

<2>The realities of this choice are familiar to contemporary women as well as nineteenth-century scholars who have long pointed out the many historical examples of Victorian working women. From biographical sketches of exceptional writers and philanthropists to historical studies on the governess, lady’s companion, or social reformer, we know a great deal about the ways the Victorian woman pursued the other side of the “apple of life.”(1) But how does this figure get written in fiction? How does a plot organize itself around female work as opposed to marriage? What kind of narrative structures allow for depicting the female epiphany of vocation, when women faced with the choice of children or great works choose the latter?

<3>In literature, the choice between marriage or work takes the form of a plot choice–either the familiar marriage plot or what I call the vocational plot. George Eliot’s Dinah Morris in Adam Bede (1856) demonstrates this choice when refusing Seth Bede’s marriage proposal to devote herself to her ministry as a traveling Methodist preacher, and later accepting Seth’s brother Adam’s proposal and giving up her literal, religious vocation for motherhood. In Margaret Oliphant’s Kirsteen (1890), the heroine refuses the proposal of an older man and earns her reputation as a mantua-maker before returning to save the family estate from financial ruin and continue to live independently. In each case, the vocational plot is perpetuated by the heroine’s choice of work over marriage. In the case of Adam Bede, the plot ends with the reversal of that choice. Nineteenth-century scholarship has well-developed insights for one side of this story–the marriage plot–but we lack a category to identify, compare, and learn from narratives that are ordered by vocational trajectories.

<4>Recent scholarship including work by Mary Jean Corbett, Kelly Hager, Claire Jarvis, Elsie Michie, Maia McAleavey, Sharon Marcus, and Talia Schaffer has deepened our understanding of the marriage plot. When parsed into offshoots that explore incest, divorce, masochism, inheritance, bigamy, female friendship, and, yes, even vocation, the marriage plot appears a rich and diverse form. And yet, the marriage plot persists as a guiding category from which these modified versions deviate and often return. On questions of marriage and occupation in Trollope, both Schaffer and Michie look to Can You Forgive Her? (1864-1865). Schaffer chooses Alice Vavasor’s story as an example of “vocational marriage,” the enveloping of a vocational plot within a marriage plot, in which the heroine is defeated in her professional aspirations and, after learning her lesson, marries a man who comes bundled with an appropriately limited job (“Why” 15). In Schaffer’s version, a woman’s quest for a meaningful career is destined to “fail;” the vocational plot is a sideshow to the stalled, but not deterred, potency of the marriage plot (“Why” 16). In drawing our attention to “recursive” thinking on the level of the sentence, Michie argues that Alice’s decision-making “temporarily arrests” courtship progress (“Rethinking” 156, 160). It’s a delay on the way to a foretold destination. Rather than providing a temporary or unsatisfying resistance to the marriage plot, this essay argues that the vocational plots of single women constitute something else entirely.

<5>The vocational plot emerged at the midcentury for single heroines, transforming the old maid–plotless and dull–into the single woman–independent and purposeful. Rather than serving as a variation on the marriage plot, these stories constitute a specific body of literature with lessons to teach us not only about the varied experiences of Victorian womanhood, but also about the shape of plots, continuance, and closure in narrative, positing the unmarried vocational woman as a surprising nexus for nineteenth-century formal experimentation. I first look at the mid-century as an important cultural-historical and literary moment for single ladies before discussing Anthony Trollope’s Miss Mackenzie (1865) as emblematic of the vocational plot and its ever-renewing, closure-resistant middle.

The midcentury old maid

<6>Finding vocational stories requires an exploration of the history and literature of that very Victorian, though apparently minor figure, the old maid. The nineteenth century is thought of as the uncontested domain of the marriage plot; as Kathy Psomiades puts it, “Marriage is the material of nineteenth-century British fiction” (53). Yet, single women are surprisingly prevalent in nineteenth-century literature. Works throughout the century, from sketches in Mitford’s Our Village (1824-1832) to Tennyson’s poems including “Mariana” (1830), “The Lady of Shalott” (1832, 1842), and The Princess (1847) to novels including Gaskell’s Cranford (1851-1853), Brontë’s Villette (1853), Yonge’s The Daisy Chain (1856), Dickens’s Great Expectations (1860-1861), Trollope’s The Small House at Allington (1864), and Oliphant’s Hester (1883) all prominently feature a female character who does not marry. A handful of minor characters who remain unmarried are hiding in plain sight in familiar works. Consider Rosa Dartle in David Copperfield (1849-1850), Marian Halcombe in The Woman in White (1859-1860), Miss Clack in The Moonstone (1868), and Ann Dorset in Phoebe Junior (1876). Reviews record the prevalence of stories about single women in now lesser-known works. The Metropolitan writes of Aunt Martha; Or, the Spinster (1843) that it aims “to show the [unmarried] state sometimes to be one of voluntary choice; and […] to display how truly amiable and useful a woman in this position of life may prove” (“Aunt Martha” 45). Another reviewer in The Athenaeum writes of The Spinsters of Sandham, a Tale for Women (1868) that its purpose is to “warn young ladies that, in the present state of society, there are not husbands enough for all, and that those who draw blanks in the general matrimonial lottery ought not to pass their lives in vain regrets” (124). Titles gleaned from such reviews–My Life and What Shall I Do With It? (1861), Olive Blake’s Good Work (1862)–tellingly pair the character of the single woman and her choice of occupation.

<7>This body of literature concentrates around a stark demographic reality; in 1851, unmarried women became a newly visible and anxiety-producing contingent of the population. The 1851 Census recorded for the first time the “Civil and Conjugal Condition” of citizens, revealing a sizable population of never-married people of both sexes, including over 1.7 million spinsters over the age of twenty and a comparable population of around 78,000 fewer bachelors (Census 36). In other words, forty-two percent of women over twenty years old in Great Britain were designated as spinsters (Census 40).

<8>Victorians reacted with dismay, disdain, and cold mathematical logic to a problem of absolute numbers. Single people (but mostly single women) threatened the cultural belief in marriage as the female vocation. This ideology is reinforced in the very text of the census report, which opens the section on marital status by stating that “Marriage is therefore generally the origin of the elementary community of which larger communities, in various degrees of subordination, and ultimately the nation, are constituted; and on the conjugal state of the population, its existence, increase, and diffusion, as well as manners, character, happiness, and freedom, intimately depend” (Census 35-36). In light of this statement on the primary importance of marriage to the happiness and success of the population, the numbers of single people recorded in the same document become an implied problem. The report describes the population of women over twenty years old in relation to men as “unnatural,” noting that the balance is the opposite in the colonies and the United States (a difference soon to shift during the course of the American Civil War) (Census 35).

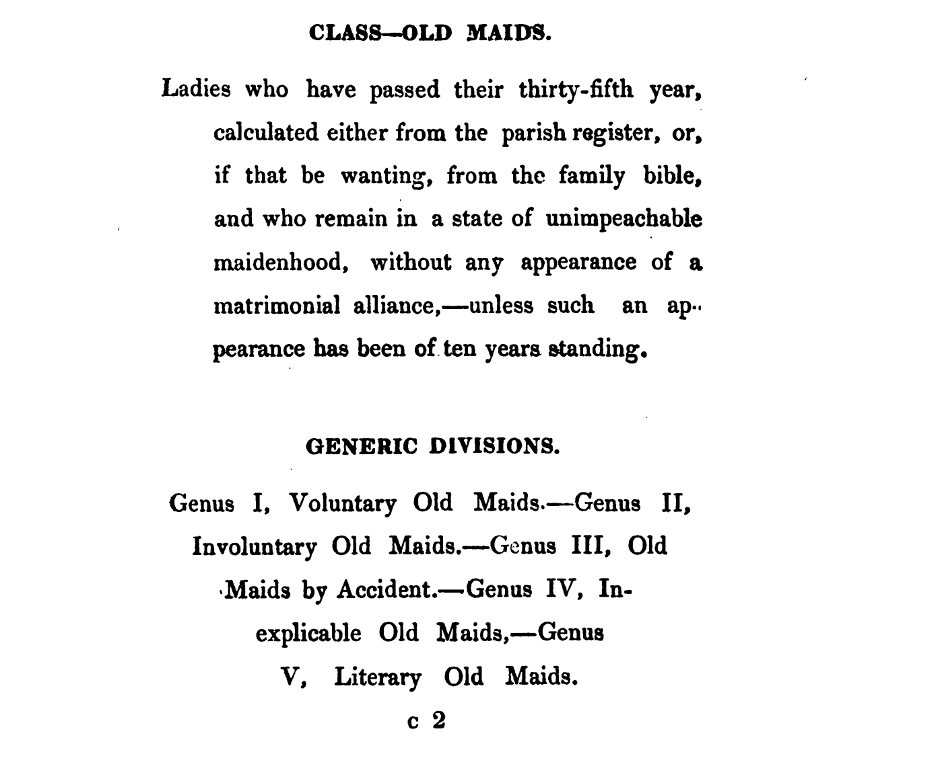

<9>Prior to the publication of the 1851 Census results in 1854, unmarried women were largely considered idle and non-threatening, calling to mind the tiresome and pitiful early nineteenth-century likes of Austen’s Miss Bates or Tennyson’s Mariana. Peter Gaskill observes the pervasive negative stereotypes in his 1835 sociological work Old Maids; Their Varieties, Characters, and Conditions. Gaskill, a journalist and briefly editor of the Monthly Magazine, styles himself as the defender of innocent celibates, intent on altering the public perception of old maids as mischievous, bitter gossips and restoring respect for unmarried women. Tellingly, of Gaskill’s five categories of old maids–“voluntary,” “involuntary,” “accidental,” “inexplicable,” and “literary”–only two are single by choice, the rest against their wishes (Gaskill 27).

<10>At the midcentury, unmarried women were alternately dismissed and studied with vehemence in correspondence to their mass, perhaps most famously by W.R. Greg. Greg’s description of these women as “redundant” in his National Review article of 1862 was the first of such language used to describe women until the end of the century.(2) Even more sympathetic responses worried that old maids lacked a natural cultural role, or at least that society couldn’t manufacture places for so many. Old maids were associated with “want of employment,” “pining away,” and the “waste of misdirected” efforts to wed (Fielding qtd. In Gaskill 1, Ritchie 318, Schooling 266).

<11>Modest titles given to life writing by spinsters, like All Right, An Old Maid’s Tale (1858), Passages in the Life of an Old Maid (1864), and My Trivial Life and Misfortune: A Gossip with no Plot in Particular, by a Plain Woman (1888) set up the generic expectation that the story of an unmarried woman’s life is lacking in plot, episodic, and dull. In conduct books, fellow old maids commiserate on a life of idleness before prescribing purpose as the antidote. Lucy Phillips, writing anonymously as “an old maid,” considers in the popular conduct book My Life and What Shall I Do With It? (1861) the problem of too much idle time: “There is, however, a wide difference between being at leisure to assist when wanted, which is our proper business, and being for ever at leisure to assist when nobody wants us, which is practically our life” (27). Endless leisure becomes a burden. Another advice book, The Afternoon of Unmarried Life (1858), is directed to author Anne Judith Penny’s fellow underemployed spinsters: “To any of you, my unmarried countrywomen, who feel the interval of time between thirty and fifty somewhat less interesting than previous years, and yourselves a little drooping under the influence of ‘Time’s dull deadening; the world’s tiring; life’s settled cloudy afternoon’ ” (29). The spinster Penny describes seems not to have benefitted much from Gaskill’s well-meaning interventions: she is bored, unoccupied, and, perhaps worse, boring, a burden.

Defining the Vocational Plot

<12>From the lethargic predictions of naysaying demographers and journalists, a new character emerges. In 1861, Frances Power Cobbe declares a widened scope of action for the single woman: “The ‘old maid’ of 1861 is an exceedingly cheery personage, running about untrammeled by husband or children; now visiting at her relative’s country houses, now taking her month in town, now off to her favorite pension on Lake Geneva, now scaling Vesuvius or the Pyramids. And what is better, she has found, not only freedom of locomotion, but a sphere of action peculiarly congenial to her nature” (Cobbe “Celibacy” 233). Cobbe’s scare quotes around “old maid” tell of a definitional shift from Miss Bates to the more modern single woman. Cobbe’s old maid is “untrammeled,” an adventurous world traveler, free. Having found “a sphere of action peculiarly congenial to her nature,” she has found a vocation. This modern old maid is a decidedly new character with a new plot–the vocational plot.(3)

<13>The vocational plot is defined by the moment of choice that occurs at its metaphorical center, in which the heroine renounces marriage and is faced with a question: to quote Brontë’s Caroline Helstone in Shirley (1849), “What am I to do to fill the interval of time which spreads between me and the grave?” (190). The answer often requires a phase of research or experimentation before committing to caring for aging parents or orphaned siblings; serving as a “maiden mother” for another’s children; participating in or running a business; working as an artist, intellectual, or writer; or participating in local or national philanthropy.(4) Often, a heroine refuses marriage and names another occupation in a single breath, as when Dinah Morris states, “My life is too short, and God’s work is too great for me to think of making a home for myself in this world,” signaling to would-be suitor Seth that his conventional familial aspirations for the two of them are directly in competition with her sense of literal, religious vocation (Eliot 32). In Charlotte Mary Yonge’s The Clever Woman of the Family (1865), Rachel Curtis declares that she must dedicate herself single-mindedly to her philanthropic pursuits at the expense of the more common pleasures of romance: “Moreover, it would be despicable to be diverted from a great purpose by a courtship like any ordinary woman; nor must marriage settlements come to interfere with her building and endowment of the asylum, and ultimate devotion of her property thereunto” (Yonge 242). Defining the vocational plot by the paired commitments to singleness and meaningful work in the center of the text, we can better recognize the affinity between these narratives of female occupation and identify a central feature of the work-oriented female narrative: it is built on accretion, succession, repetition; it is defined by middles, rather than by endings.(5)

<14>Admittedly, seeing central events as definitive goes against how we classify plots and our most basic reading practices. Plot, from Aristotle to Peter Brooks, is linear, forward moving, and end-oriented. Reading for the plot is often synonymous with reading for the ending. Instead, I propose reading for the middle, a nonlinear method that prioritizes moments of discernment and conflict, and treats middles with the same sustained gravity and attention we reserve for endings. Reading this way treats middles like endings. In the case of some examples I’ve already mentioned, like Adam Bede or The Clever Woman of the Family, this necessitates downplaying the marital finale as a purposefully unconvincing concession to convention, both generic and societal, and reading the narrative as primarily a novel about a woman’s quest for meaningful work, a vocational plot. To put that another way, non-linear reading allows us to see vocational plots as not another version of the marriage plot, but something else entirely.(6) When we read these stories outward from the middle, prioritizing the most radical and unresolved moments, we are able to reconstruct a single woman’s narrative in the nineteenth century.

<15>Anthony Trollope’s Miss Mackenzie is one example of a novel that challenges that narrative of the plotless old maid with successive, multiple, and simultaneous marriage and vocational plots that refuse the choice between marriage and work seen in the opening quotes.(7) Miss Mackenzie explores the formal and ideological possibilities of different permutations of female plots: mission then marriage, successive missions then marriage, alternating mission and marriage. Unlike those women who are offered the choice of the halves of the apple of life, Margaret Mackenzie is allowed successive and simultaneous plots, demonstrating the abundance of singular stories.

<16>In addition to serving as a rich example of the vocational plot, Miss Mackenzie is also, significantly, a minor work. In the same way that historical old maids were relegated to the fringes of society, the literature of single women is often peripheral to the canon. When reading for the vocational plot, many fitting examples are found among the least known works of lesser known novelists, or forgotten works by forgotten writers. Defining it as a vocational plot allows us to see Miss Mackenzie as part of a larger conversation in the midcentury with such canonical texts as Cranford, Villette, and Adam Bede and attaches it to other more minor (though hugely popular in their own day) examples like Miss Marjoribanks, The Clever Woman of the Family, and The Daisy Chain. The vocational plot allows us to reunite the literature of single woman and begin to work through its importance.

Trollope’s Miss Mackenzie: Proposals and Professions

<17>Miss Mackenzie begins with an unusual protagonist–a single woman of thirty-five who spent the last fifteen years caring for her invalid brother. His recent death leaves Margaret in possession of a considerable fortune. Reviewers were almost uniformly surprised (and dismayed) by Margaret’s age. “Our most popular novelist,” goes one review, “has devoted two volumes to the outer and inner history of an excellent spinster of five-and-thirty” (“Belles Lettres” 283). The London Review agrees that it is “bold” for Trollope to ask readers to care about an old maid, continuing that, “Few writers could have imagined such a heroine” (“Miss Mackenzie” 387). Though not often the subject of scholarship, those who write on Miss Mackenzie also focus on the unlikeliness of Margaret as a protagonist due to her age.(8) However, focus on the choice of a thirty-something protagonist as the innovation of Miss Mackenzie distracts us from Trollope’s other formal innovations–his experiments with the vocational plot–made possible by Miss Mackenzie’s unconventional character.

<18>The novel is aware of the expectations for narratives about single women–seen in Gaskill and Greg’s accounts–for which Trollope references Tennyson’s “Mariana” as a shorthand. Frequent references to “Mariana” suggest, falsely, that Margaret’s story is confined to idleness, especially the fifteen years spent caring for her brother before the novel opens:

her life had been very weary. A moated grange in the country is bad enough for the life of any Mariana, but a moated grange in town is much worse. Her life in London had been altogether of the moated grange kind, and long before her brother’s death it had been very wearisome to her. I will not say that she was always waiting for some one that came not, or that she declared herself to be a-weary, or that she wished that she were dead. But the mode of her life was as near that as prose may be near to poetry, or truth to romance. (Trollope 5)

The playful borrowing of Tennyson’s language (“weary,” “moated grange”) quickly establishes the conventions for Victorian singleness that Trollope exposes as lacking. Comparison to a stanza from Tennyson’s poem shows that prose can be only so similar to poetry. The narrator’s colloquial tone in phrases like “bad enough” and “much worse” in the novel sounds decidedly different from Tennyson’s verse: “Her tears fell ere the dews at even;/ Her tears fell ere the dews were dried” (Tennyson). The narrator’s syntax–“I will not say that she was always waiting for someone that came not”–is purposefully and playfully artless compared to “he cometh not, she said” (Tennyson). In prose form, the rhythmic repetition of Tennyson’s poem looks meandering, and according to one reviewer, Trollope’s novel is a “monstrously prosaic version of Mariana in the moated grange” (“Miss Mackenzie” 265). “Prosaic” is also the word Juliet McMaster uses to describe Margaret’s lot in her introduction to Miss Mackenzie: “In aligning Margaret Mackenzie’s story with those of Griselda, and Cinderella, and Mariana, … Trollope is making clear his vision of the potential for romance in the most prosaic and mundane lives” (unnumbered). While explicit comparison to “Mariana” invites a description of Miss Mackenzie as dull compared to Tennyson’s verse, a “monstrously prosaic” version of a prosaic life dares to claim that the “ordinary” is not so. Trollope’s indulgently lengthy narrative of an old maid makes the case that Margaret’s story is worth narrative space and readerly attention. By choosing a middle-aged spinster for his protagonist, Trollope invites readers to rethink preconceptions of single women in prose.

<19>The narrator’s fears for Margaret’s plot potential are echoed by her family, who: “had declared her to be a silent, stupid old maid. As a silent, stupid old maid, the Mackenzies of Rubb and Mackenzie were disposed to regard her” (Trollope 9). Margaret worries similarly about her own affinity to Tennyson’s Mariana, explicitly working to avoid the “lifeless life” that so many expect of her (Trollope 26). In free indirect discourse, Margaret considers, but dismisses, the possibility of befriending a clergyman, giving all her inheritance to the charity of his choice, and declaring her dotage:

Would it not have been easier for her–easier and more comfortable–to have abandoned all ideas of the world, and have put herself at once under the tutelage and protection of some clergyman who would have told her how to give away her money, and prepare herself in the right way for a comfortable death-bed? There was much in this view of life to recommend it. […] But in order to reconcile herself altogether to such a life as that, it was necessary that she should be convinced that the other life was abominable, wicked, and damnable. (Trollope 27)

The refrain of “easy” and “comfortable” implies the conventionality of this narrative mode, the story of the single woman too afraid to handle her own affairs–like Miss Matty, who Mary Smith and her father carefully shield from knowledge of her real financial situation in Cranford–and Margaret’s futile attempts to convince herself of the appeal of ease and comfort at the expense of plot.(9) Margaret is offered two options: a watered-down version of a charitable vocational plot where all of her action is handed over to a clergyman and his wife, and “the other life” in the world.

<20>Instead of abdicating her money and her plot, the chapter “Miss Mackenzie Commences her Career” opens a story that alternates between potential marriage plots and other plots–most of which remain incomplete. A brief summary illustrates the fullness of Margaret’s plot in contrast to Mariana-like expectations. After her elder brother’s death, Miss Mackenzie takes lodging in Littlebath and brings along her niece Susanna, whom she promises to educate, and, if Margaret should marry, whom she promises to provide with 500 pounds. Margaret also invests in her brother Tom and Mr. Rubb’s business (Rubb and Mackenzie), advancing them a large sum on the faith of the family before mortgage papers can be made out. Over the holidays, she travels to visit her cousins the Balls in London. The widowed John Ball proposes to Margaret. She refuses him (much to his mother’s dismay, since he and his nine children could benefit from Margaret’s money) because she does not love him. During this trip, she learns that her money has been mismanaged by Tom and Mr. Rubb, but generously considers it a gift to her brother.

<21>Upon returning to Littlebath, Margaret is pursued by a local man, Mr. Maguire, and her brother’s business partner, Mr. Rubb. As she considers the attractions and (considerable) drawbacks of both potential marriages, Margaret gets a telegram that her brother Tom is dying. She returns to London where she learns that her investments with Rubb and Mackenzie are lost. Her responsibility to her brother’s family combined with her financial losses make marriage an impossibility. She recommits herself to singleness and using what is left of her fortune to care for Tom’s family. In a further twist, Tom’s death precedes the revelation that there has been a mistake with her inheritance: her fortune rightfully belongs to John Ball. John offers to marry Margaret for love even if she is now a pauper and she readily accepts. However, Mr. Maguire arrives from Littlebath claiming that he and Margaret are engaged. Though Margaret attempts to clear her name of this false charge, Sir John’s lukewarm reaction leads her to assume that her engagement to him is broken. She goes to live with a former servant. Mr. Maguire publishes in the local paper accusing John Ball of swindling Margaret out of her inheritance, making a resolution appear even less likely. However, a distant cousin facilitates a reconciliation between Margaret and John and the two are married.

<22>This ending goes against Trollope’s own explicit attempt to write “with a desire to prove that a novel may be produced without any love” (Autobiography 118). Trollope abdicates responsibility for the direction of his plot, suggesting that the marriage plot ideology is so overwhelming that the novel concludes that way despite his best efforts: “even in this attempt it breaks down before the conclusion. In order that I might be strong in my purpose, I took for my heroine a very unattractive old maid, who was overwhelmed with money troubles; but even she was in love before the end of the book, and made a romantic marriage with an old man” (Autobiography 118-119). By highlighting a “breakdown” before the conclusion, Trollope encourages us to read non-linearly for the moment where Miss Mackenzie’s story veers from unconventional to conventional, allowing us to see beyond or around the marital ending to the vocational plot.

“Not Perfect or Whole”: Margaret’s Vocational Plots

<23>The superfluity of suitors in a novel that claims to attempt to avoid a love plot is at first curious. Why suggest so many romantic options when refusals are inevitable? When presented with her first proposal from an old lover, Margaret is “not prepared to sacrifice herself and her new freedom, and her new power and her new wealth, to Mr. Harry Handcock” (Trollope 12-13). The listing of repeated “and her new” makes explicit all she has gained, and all she has to lose by marrying so early in the narrative. Refusing Harry Handcock launches Margaret on her first vocational plot, in which she joins the ranks of Littlebath bluestockings. Later, Mr. Rubb’s proposal only confuses Margaret’s professional relationship with him, in which he mismanages her investments. In fact, a pattern develops in which, rather than providing a marriage plot, suitors create other plots for Margaret: rather than accepting Harry Handcock, Margaret becomes a patron aunt; rather than accepting John Ball, Margaret endures a disinheritance plot; rather than accepting Mr. Rubb, Margaret enters an investment plot, and rather than accepting Mr. Maguire, Margaret is involved in a periodical scandal.(10)

<24>The suitors Margaret refuses are not depicted as attractive, further supporting the importance of vocation in the story. When she considers the choice of Mr. Rubb or Mr. Maguire, Margaret is satisfied for the option, “Miss Mackenzie […] told herself that she might have a husband if she pleased,” but is flummoxed by both of their considerable flaws: “but then, which should it be? Mr. Rubb’s manners were very much against him; but of Mr. Maguire’s eye she had caught a gleam as he turned from her on the doorsteps, which made her think of that alliance with dismay” (Trollope 149). The successful suitor, John Ball is introduced with tepidity as well. Margaret’s initial refusal of John Ball is simply and convincingly that she does not love him. The only attraction of the match is the work it offers in the form of nine children:

It would be very sad to be the wife of such a man; it would be very sad, if there were no compensation; but might not the sacrificial duties give her that atonement which she would require? She would fain do something with her life and her money–some good, some great good to some other person. […] But there was no doubt that she would do good service if she married her cousin; her money would go to good purposes, and her care to those children would be invaluable. They were her cousins, and would it not be sweet to make of herself a sacrifice? (Trollope 111)

Margaret seeks meaningful work–“some good” or “service”–over romantic connection, even in marriage.

<25>Margaret’s ambivalence about her suitors is starkly contrasted with her “natural” affinity for and “satisfaction” in nursing (Trollope 181, 183). Margaret easily and even gratefully returns to the role during Tom’s illness:

As she sat but his bedside, night after night, she seemed to feel that she had fallen again into her proper place, and she looked back upon the year she spent in Littlebath almost with dismay. Since her brother’s death, three men had offered to marry her, and there was a fourth from when she had expected such an offer. She looked upon all this with dismay, and told herself that she as not fit to sail, under her own guidance, out in the broad sea, amidst such rocks as those. Was not some humbly feminine employment, such as that in which she was now engaged, better for her in all ways? Sad as was the present occasion, did she not feel a satisfaction in what she was doing, and an assurance that she was fit for her position? […] She told herself that it was so, and that it would be better for her to be a hard-working, dependent woman, doing some tedious duty day by day, than to live a life of ease which prompted her to longings for things unfitted to her. (Trollope 191)

It is easy to put most emphasis on the phrase “she told herself” and dismiss this speech elevating purposeful occupation over the quest for romance as so much self-comfort in the face of disappointment. Yet phrases like “proper place,” “satisfaction,” and “fit for her position” herald the serendipity of vocation that are absent from the love plot.

<26>If nursing two brothers seems like sacrifice rather than calling, Margaret nurtures quiet artistic aspirations during both of her caregiving stints, doubling her vocation as selfless service and self-expression. In the years spent nursing her older brother she writes, “quires of manuscript in which [she] had written her thoughts and feelings–hundreds of rhymes which had never met any eye but her own” going on to note that she has also written “outspoken words of love contained in letters which had never been sent” (Trollope 9). She rediscovers the remaining pages when caring for Tom:

She had brought a little writing-desk with her that she had carried from Arundel Street to Littlebath, and this she had with her in the sick man’s bedroom. Sitting there through the long hours of night, she would open this and read over and over again those remnants of the rhymes written in her early days which she had kept when she made her great bonfire. There had been quires of such verses, but she had destroyed all but a few leaves before she started for Littlebath. What were left, and were now read, were very sweet to her, and yet she knew that they were wrong and meaningless. What business had such a one as she to talk of the sphere’s tune and the silvery moon, of bright stars shining and hearts repining? […]

And yet she loved them well, as a mother loves her only idiot child. They were her expressions of the romance and poetry that had been in her; and though the expressions doubtless were poor, the romance and poetry of her heart had been high and noble. (Trollope 191-192)

The love she expresses returns us to the language of vocational service; Margaret is a virgin mother to a needy child. It is notable that we have heard of these papers only once before (after her first brother’s death) and yet they have traveled to Littlebath, and now the Mackenzie home. Margaret’s artistic ambitions are suggested to run always under the surface. Her interconnected, multilayered vocations, not always visible to the reader, suggest the rich, vocational life that could be mistaken for prosaic, because it is not always readily transcribed to prose. These papers represent both the artistic inner life Margaret harbors, and her hopes of a future romantic plot. When she tears them, she rededicates herself (yet again) to single life. Doubling vocations–Margaret is at once a caretaker and a struggling artist, and as an artist a caretaker of fragile, newborn verse–puts almost excessive pressure on the vocational plots of single women. Unmarried, Margaret has not one, but two plots at a time. This excess is characteristic of Margaret’s story: she cares for not one, but two brothers; she discards and destroys her verse not once, but twice; she receives not one, but four proposals, many of them repeated; she reconsiders and then renounces her marital aspirations not once, but multiple times; and she moves in and out of fortune. Rather than conforming to the idleness of “Mariana” as predicted at the outset, Margaret has a plot that exceeds her family’s knowledge and expectations, and the reader’s, too.

<27>Miss Mackenzie’s circumstances, and the plot, change again when she learns she is disinherited. Margaret begins the vocational plot once more, in this version, she is poor, friendless, and looks for a wage-earning occupation rather than a vocation. Nursing crosses that boundary, too: “She had declared to herself but lately that the work for which she was fittest was that of nursing the sick. Was it not possible that she might earn her bread in this way?” (Trollope 239). Each time Margaret is pulled away from a marriage plot, she considers a vocation–caregiver, companion, nurse, writer, investor–allowing her to explore the myriad options available to single women. The narrator declares, perhaps ironically, that though, “There is, I know, a feeling abroad among women that [they should] learn to take delight in the single state,” the “truth of the matter” is much simpler: “A woman’s life is not perfect or whole till she has added herself to a husband” (Trollope 136). The full-to-bursting plot of Miss Mackenzie suggests that Margaret’s single life is not “perfect or whole” because it lacks something, but because it exceeds generic boundaries of marriage or vocational plots.

<28>When John Ball repeats his proposal, the romantic question is resolved in the language of work: “‘You want to be a nurse; will you be my nurse?” (Trollope 270). The proposal promises to unite the “work for which [Margaret] is fittest” with matrimony. Yet this successful proposal is followed by a long interval in which the novel resists the happy conclusion it has apparently chosen. Margaret assumes that Mr. Maguire’s false claims have ruined the engagement as the novel also struggles to overcome Margaret’s initial and decided disinterest in John Ball as well as the role of money in their pairing. An entirely new character arrives to resolve these difficulties. Clara Mackenzie, a cousin who neither Margaret nor the reader has ever met, arrives at Margaret’s door sixty pages from the end of the novel. Clara uses the fairytale language of another genre: “And now I have heard this wonderful story about your fortune, and about everything else, too, my dear; and it seems all very beautiful, and very romantic; and everybody says that you have behaved so well; and so, to make a long story short, I have come to find you out in your hermitage, and to claim cousinship, and all that sort of thing” (Trollope 341). Clara rewrites the story from vocational saga to neat romance with words like “very beautiful,” “very romantic,” and “all that sort of thing,” and indeed has the role of “mak[ing] a long story short.” Clara pushes Sir John to set a date within six weeks, prompting him to think, “When he had left his home this morning he had not fully made up his mind whether he meant to marry his cousin or not; and now, within a few hours, he was being confined to weeks and days!” (Trollope 398). To make room for John Ball’s halting decision process about whether he will marry Margaret, Margaret’s perspective fades from the final pages. She declares her love, but little about how this change of heart occurred. We are left to wonder at the letdown from the vocational language of nursing. Clara Mackenzie’s role is to affect a marriage plot ending, however improbably, and she continues to use turns of phrase that summarize and dismiss, telling Margaret, “the long and the short of it” and encouraging readers to accept the change of heart that both Margaret and John must have undergone (Trollope 342).

<29>Margaret’s final role as nurse and wife begs a comparison to that other famous nurse-wife, Jane Eyre. In the conclusion to Brontë’s novel, Jane tells readers that nursing Rochester occupies all her “time and cares” (542). Jane admits, after claiming that she and her husband are perfectly united, that her experience of nursing him is not as complete as he thinks: “And there was a pleasure in my services, most full, most exquisite, even though sad–because he claimed these services without painful shame or dampening humiliation. He loved me so truly, that he knew no reluctance in profiting by my attendance: he felt I loved him so fondly, that to yield that attendance was to indulge my sweetest wishes” (Brontë 544). Is it not her sweetest wish? Should Rochester know reluctance and feel shame? Jane’s hesitation regarding her own fulfillment stands in contrast to her certainty about St. John Rivers’s vocation with which the novel closes, “unclouded” and “undaunted” (Brontë 545).(11) To “profit” from a wife’s services mixes the language of work and romance. John Ball’s easy solution that Margaret can be both nurse and wife belies the uneasy combination of work and marriage.

<30>While Margaret doesn’t end the novel with the vocational certainty of St. John Rivers, the late and limping marriage returns readers to the more certain moments in the novel–those where Margaret considers what she wants to do with her considerable newfound freedom and provides her own answers. As one fictional example of the old maid of 1861, Margaret Mackenzie defies conventional notions of old maidishness and suggest that plots organized around female work take on a different form than those teleologically building toward marriage. Margaret explores, experiments, tests. She makes decisions in mid-narrative that change the course of her story. She is, like Cobbe’s old maid, “untrammeled,” moving freely between Littlebath and the homes of friends and family in London. She does find a role–nursing–that is especially “congenial to her nature.” If Miss Mackenzie fails in avoiding the romantic plot altogether, it succeeds in simultaneously suggesting an alternative.

Conclusion

<31>Despite the victorious promise of Frances Power Cobbe’s “Old Maid of 1861,” the spinster as a cultural figure is still haunted by the marriage plot and the nineteenth century. Two recent works on single women bemoan the fact that stories of fellow singletons are few and far between. Kate Bolick’s Spinster (2016) often looks to the nineteenth century as it attempts to “think beyond the marriage plot,” claiming that the spinster has not gained status since the Victorian era (160). Rebecca Traister begins All the Single Ladies (2016), her study of how single women have changed American politics and culture, with similar frustrations with the pesky and persistent marriage plot, noting her childhood disappointment when favorite, independent heroines including Laura Ingalls, Jo March, and Anne Shirley married: “the tale that was worth telling about her was finished once she married” (1). Connecting these contemporary accounts to the “Old Maid of 1861” suggests that stories about vocational single women are not absent, but waiting to be made visible and connected as a literature of their own. In a letter of 1846, Charlotte Brontë writes to Miss Wooler, “I speculate much on the existence of unmarried and never-to-be married women nowadays” (Brontë Letters 448). It is time that we do, too.