<1>Late in 1889 when Katharine Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper—writing collectively under the pseudonym “Michael Field”—were immersed in the research for their early verse drama The Tragic Mary, the two women visited a wax museum of the Stuart monarchy above one of the chapels in Westminster. The site was one of a variety of sources that the Fields used for their research on Mary Queen of Scots. In her journal, Cooper recounts her abhorrence at this eerie memorial. “It is a weird, desolate little chamber,” she writes. “[Y]ou are saddened by the dusty finery of robes & paste-jewels, by fixed faces, the closed & opened eyes—the garishness & ruin” (Works & Days, 114). At the heart of her critique is a fundamental disagreement with the museum’s conception of the past. Even as its curators revived the monarchy for late Victorian visitors, the museum simultaneously marked the Stuarts as forever lost. By attempting a high level of specificity—the finery, the robes, the jewels, the detailed faces—the museum froze these figures at a particular biographical moment, fashioning them according to their own ideologies. These monarchs never absorb the visitor in the queens’ lives or transport them to the past. The visitor remains separate from these objects by the visible dust and ruin that mark the gap in time. The fixed faces, the eyes either permanently open or closed, underline that interaction is impossible. In the museum, the past is at the whim of the designer’s interpretation and unchangeable for future reimagination.

<2>The Tragic Mary responds to this desire to freeze the past and offers a feminist challenge to historical recovery. Since the author’s individual enthusiasm structures nineteenth-century histories, the individual subject position of the historian, who was typically male, mediates historical engagement. Thus, historians might strive to offer an authentic glimpse into the past, but their recovery of the past is often partial, incomplete, and biased, especially when it comes to depictions of self-possessed women. Bradley and Cooper use the verse drama to experiment with an alternative method of representation. By employing the temporal and physical attributes of theater in the text, the Fields create a hybrid form that transcends print production’s own limits in memorializing and historicizing women, allowing the protagonist to exist outside the space and time of one inscription. The Tragic Mary circumvents the problem of the historian’s bias by invoking the embodied, affective nature of theater and notions of theatrical time, writing in gestures to replay, repetition, and return, and nods to the participation of future audiences. In this way, the drama envisions a new type of historical recovery—a process that is collaborative rather than possessive and that honors affect as a crucial aspect of memory.

<3>This argument participates in a renewed critical engagement with the duo’s poetic dramas. Even as Michael Field has emerged as a writer worthy of space in contemporary scholarship, the amount of writing on their drama pales in comparison to their poetry. No doubt, like the Fields’ contemporaries, we might be prone to dismiss these dramas as antiquated and confusing.(1) However, just as separating out Bradley’s contribution from Cooper’s does a disservice to their unique artistic collaboration, separating out their identity as poets from their identity as dramatists creates interpretative problems, especially since the pair considered themselves dramatists first and foremost. Recent strides have attempted to balance this disparity: both Andrew Eastham and Heather Bozant Witcher have acknowledged the importance of reading the Field’s plays as drama. Witcher in particular pauses on the genre of the poetic drama in the late nineteenth century and urges critics to recognize it not as a generically confused oddity but as a deliberate formal experiment (513).

<4>Following this train of thought, it is worthwhile to consider how verse dramas draw on the characteristics of the theater as well as the traditions of poetry. The Fields wanted their plays performed, and their next play, A Question of Memory, received a one-night performance at the Independent Theatre on October 27, 1893. Although the play’s biting critical reception stopped the Fields from pursuing production of another work for the stage, The Tragic Mary is one of the last plays they wrote before their affinity with the stage ended, so it makes sense to read this drama as a discourse with embodied performance as well as with Victorian poetics. Drawing on performance studies, I explore the way three elements of performance—affect, embodiment, and time—appear and function in the text to create a dialogue with and an expansion of the capacity of the printed book. The Fields challenge historical recovery, but they also find a new use for the verse drama form, one that embraces its identity as both a text for solitary reading and a script meant to be performed.

Faux Fur & Marble Tombs: Affective Engagement with Objects

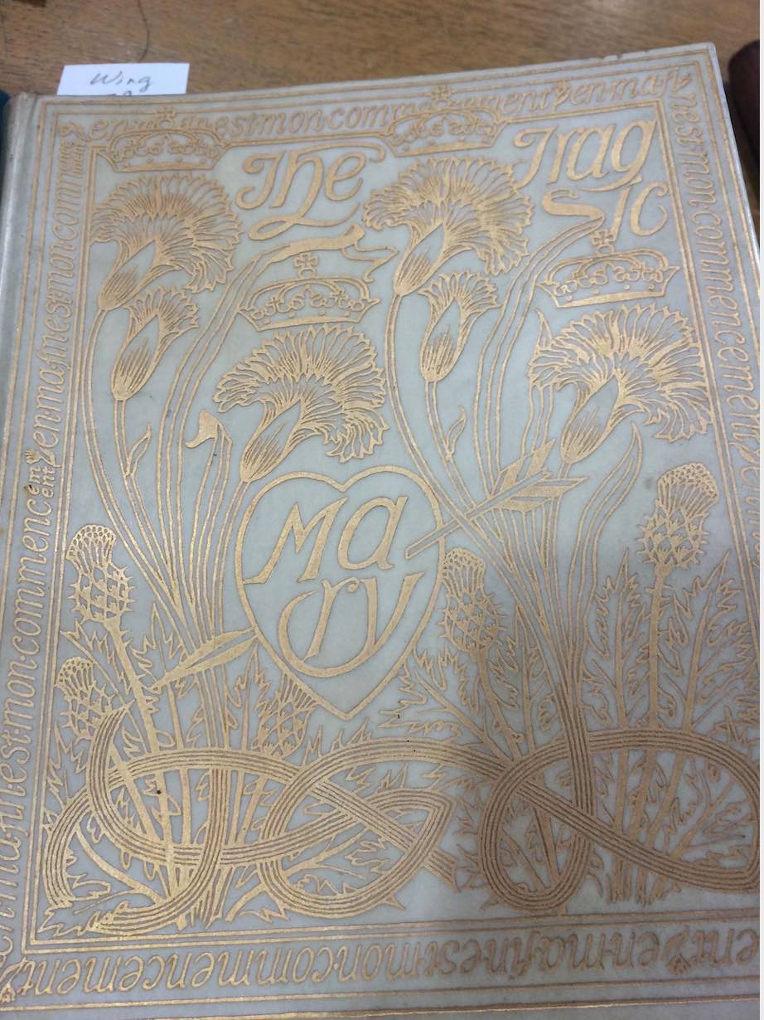

<5>With The Tragic Mary, the Fields produced not only a historic retelling of Mary Queen of Scots, but also a visually beautiful book. Oscar Wilde, known for his own ornate and limited-edition collection of poems published by Bodley Head in 1892, praised its appearance as one of the most beautiful books of the century (qtd. in Works and Days 139). Its first edition, published by George Bell with cover art commissioned from Selwyn Image, included only 60 copies on vellum with a stark white cover reminiscent of a marble monument. The front features gilt writing announcing the title of the work in the center and the French phrase “En ma fin est mon commencement” (“In my end is my beginning”) circling the border (fig. 1). Intricately designed books with close attention to page presentation and cover art were popular amongst writers of the late nineteenth century, not just the Fields. As Joseph Bristow notes in his examination of fin-de-siècle book art, these objects asked for a different type of aesthetic contemplation as readers were meant to envision the cover as an art piece equal to the artistry of its contents (16). The Tragic Mary is no different in this regard; the artistic choices of the book design ask the audience to reconsider the historical study that transpires in its pages.

<6>Even though it is a drama, in its attention to the object design, the Tragic Mary’s appearance seems to mark it as a book to be read rather than a script to be performed. In the nineteenth century, a sharp divide existed between literature and theater, especially in regard to its physical manifestation. The line between “literature” and “theater” depended on the text’s material condition more so than any linguistic quality, and play scripts were typically printed as acting editions on and with inexpensive materials (Guy & Small 4). Literary words remain and are cherished whereas theatrical scripts were a means to an end, discarded as soon as the performance run ended. The former textual object is static and timeless; the latter can be reinterpreted for each new performance and might only exist for a finite amount of time.

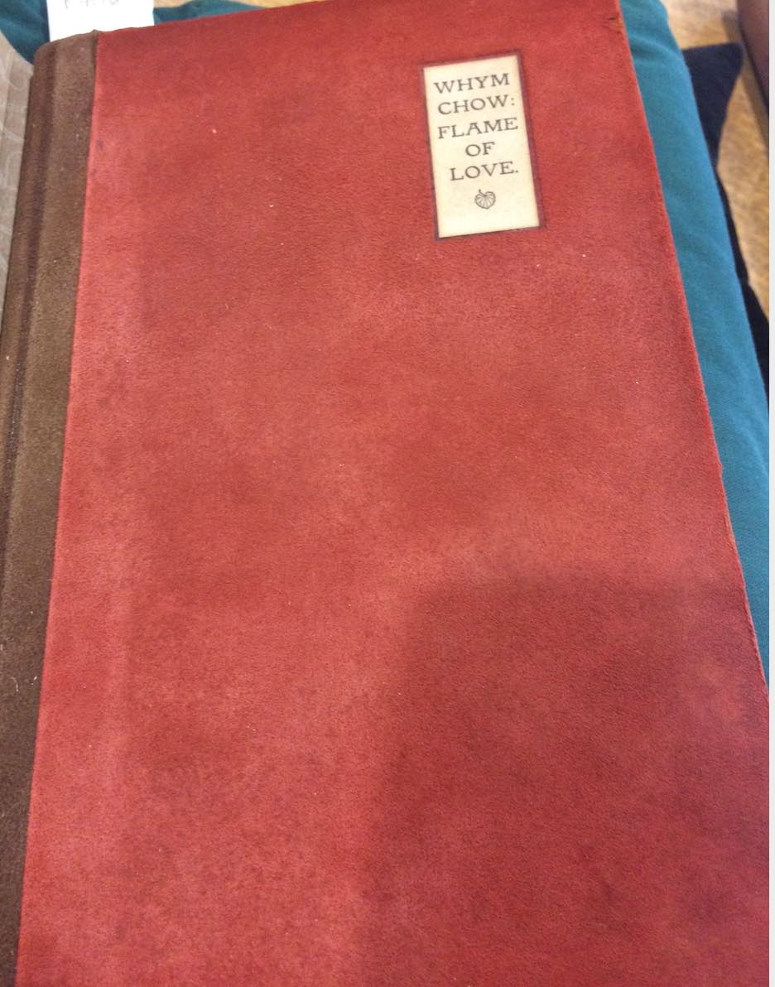

<7>Yet, the Fields used objects, including books, to not just remember the past as it happened but to reawaken it, and The Tragic Mary, seen in this context, becomes more than just a definitive, static historical interpretation. The book-object holds a liminal position that both remains and is transitory: it is the audience’s invitation to collaboratively reimagine Mary with the Fields. Bradley and Cooper used particular objects to commemorate those they loved. The Fields endured many deaths among their close family: Bradley’s mother died in 1867; her sister, and Edith’s mother, Emma Cooper died in August 1889; Cooper’s father fell to his death on holiday in 1897; and Bradley and Cooper lost their beloved dog Whym Chow in 1906. Loss affected Bradley and Cooper deeply, yet they found methods to immortalize those who passed including crafting shrines for their loved ones (Maxwell 32). The 1850s and 60s was an era of relic obsession, but whereas relics serve as “the material sample of a being that will never be given to grow, or seen or felt again,” the Fields use commemorative items to reanimate their lost ones and facilitate a communion outside of mortal time (Lutz 135).(2) Nowhere is this more apparent than in the book of poems the Fields wrote after their dog’s death, titled Whym Chow: Flame of Love, which was bound in brilliant red, faux dog fur (fig. 2). The sensory experience of handling this book makes the reader feel as if they are petting a dog, but not to resuscitate the dog exactly as he was. Instead, the work encourages the reader to recall the affect associated with his presence, and the Fields use the text to envision a world outside time where the three of them—Bradley, Cooper, and Whym Chow—exist as a type of Holy Trinity.

<8>The Fields used this same tactile affect in The Tragic Mary’s composition. Although they engaged extensively in textual research, the Fields composed Tragic Mary mainly by visiting historical sites important to Mary’s life and interacting with the queen’s material possessions. They allowed the history to speak to them from a variety of sources, most of which were not textual. In addition to the wax museum, the pair visited castles, towns, sites Mary frequented, and her tomb in the Lady Chapel of Westminster Abbey. In their preface to the drama, they specifically recall their memory of touching “the very silks that Queen Mary handled,” saying that “an impulse transports us: we are started on an inevitable quest” (v). What happens to them is a sort of affective transfer—by handling Mary’s possessions or inhabiting the places she inhabited, they become attuned to her spirit. Importantly, the Fields never portray this experience as some kind of time travel that affords them the opportunity to see exactly who Mary was. The objects do not allow the Fields to know Mary. The word “quest” and, in their journals, their expression of being “on the track of Queen Mary” displace knowing and forefront feeling (Binary Star 106). These places and objects are not just historically informative; they are a way to commune with the dead. It is the affect, unbound by time, that structures the history.

<9>The beginning of the drama leaves space for the audience’s affect in the construction of Mary’s identity, as Mary remains decidedly silent and thus absent from the text. The play commences with only mentions of Mary and not the dramatis persona herself. It is not until scene three of the first act that Mary appears on the “stage.” Instead, the opening bombards the reader with a series of men constructing fates and plots for her. The Earl of Bothwell, recently banished by the queen, asserts that he will wed the woman who put him into exile, despite her marriage to Lord Henry Darnley. “She banishes me,” Bothwell bemoans in the first line of the play, but after revealing his plan, reestablishes himself as the subject and her as the object: “I shall win her!” (1). Her husband, Henry Darnley, similarly constructs a fate for Mary in the first scene. The audience meets Darnley right after he, alongside a contingent of Protestant lords, have murdered Mary’s favored secretary, David Riccio, in front of her at Holyrood. Darnley explains his will to gain the matrimonial crown from Mary (which would grant him kingship should she die before him), and the co-conspirators, Morton and Ruthven, desire an end to Mary’s Catholic rule.

<10>During this time, Mary remains tucked away in her private chambers, unaffected by these machinations. Mary’s absence might be read as passivity, proof that she will be at the mercy of these men, especially if she is read alongside of Swinburne’s verse drama trilogy about Queen Mary, as the Fields’ contemporaries most likely would have.(3) Swinburne’s Mary longs to be a man (claiming that it will make her “all ways better than I am” [53]), flirts with her entourage of love-struck men, and sentences a man to death while concealing her power and intelligence with repeated comments about women’s weaknesses. The Mary of Michael Field might strike the late nineteenth-century reader as ineffectual after they encounter the Mary of Swinburne who, as Jayne Elizabeth Lewis states, exhibits “female authority” amidst “infantile male subjectivity” (193).

<11>However, Jill Ehnenn reminds us that silence can be a source of power in drama. Pointing to the use of this tactic in Elizabeth Robins’s and Florence Bell’s play, Alan’s Wife, and in the Field’s own drama, A Question of Memory, Ehnenn states that these moments of nonacting “are performative, they do something; like the negative performative speech-act ‘count me out,’ these silences are calculated performances of refusal that demand a response from the audience” (100). When Mary remains silently behind a door that Darnley and his courtiers cannot access, it is not ineffectual, but a choice that has consequences. As Darnley notes, her refusal to engage with him means she chooses not to align herself with him: “She would not lift her hand to succor me” (14). While in text silences are absences, in performance they are not. Mary’s silences and refusals are felt by the men on stage. When Mary refuses to open her chamber door to Darnley, Bothwell, Morton, and Ruthven who wait outside, it enrages them and fuels their plot, demonstrating the power of her refusals and silence and the subsequent lack of power these men possess. It propels these men to seek Mary’s submission as she refuses to adopt the role of the vindictive ruler or the submissive wife.

<12>To be fair, in The Tragic Mary, Mary does not remain altogether silent at the beginning as these men weave their plots. She becomes very present on stage, or in the pages of the book, through her piercing laughter, at which Bothwell jumps and Darnley sickens (1, 4). After her marriage to Bothwell later in the play, her “black weeping” functions as another nonverbal cue that baffles and frustrates him (222). Her glances, her smiles, the movements of her hands, and her facial expressions all become data for the men surrounding her to interpret, which they do without end. Even if characters witness her physical and gestural clues, they are often poor readers of her demeanor, and what they commit to speech, and subsequently to print, cannot be trusted. Bothwell, for instance, tells Morton that the queen has promised herself to him not through, as Morton asks, her own writing, but through “her great, / Committing glances” even though Mary entertains little ideas about their marriage (118).

<13>For the characters in the play then, Mary’s silence and nonverbal vocalizations have presence and power. Often this means that the men project onto her actions their own agenda: the self-conscious Darnley interprets Mary’s actions as deliberate snubs, and the power-hungry Bothwell reads them as flirtatious advances. But what response must the audience have to these silences? With competing interpretations of Mary’s actions by biased men and no clarifying stage directions, the audience has even less knowledge about Mary. Her representation depends on an embodied performance that the reader cannot experience. Silence has the potential to carry Mary’s spirit unfiltered into the audience’s minds. The silence asks the reader to embark on a journey to discover Mary; the book needs the reader’s participation, their affect, to complete her portrait. The drama relies on an affective connection between audience and subject—much like a theatrical performance does—to create the history. Some part of Mary remains off the page and in the hearts of its readers. By making the physical nature of performance crucial for this text, The Tragic Mary showcases the limits of textual inscription in capturing Mary but also demonstrating the way the page can invoke some of that affective engagement of embodied performance.

<14>The text’s dependence on the reader’s affect demonstrates that affect is not just the purview of the theater and not opposed to historical and literary endeavors. Theater tends to be associated with affect because of its liveness, its ability to come to life and demand that the audience feel something while sharing the space with another’s body and story. Yet, as performance studies scholar Rebecca Schneider points out in her discussion of the disciplines of theater and history, written documents also contain this potential for liveness because affect exists in objects and writing, and “material can ‘come alive again’ in an archive as well as on stage” (44). Holding an object and interacting with it is not a neutral undertaking nor can we, as embodied humans, ever shed our own embodied reality when we look into the past. The Fields play with the affect buried in objects within The Tragic Mary. Although seemingly static, unchanging, not “live,” the text carries with it the potential for animation. The book itself cannot capture Mary, but it facilitates the reader’s process of remembering. By building performance into the text, not just writing a historical interpretation that happens to be a drama, the Fields create a living book that invites collaboration, imagination, and the interpretative heart of the audience to create history.

<15>It is no coincidence then that the object of the Tragic Mary mimics a tombstone. The Fields envisioned marble sculpture as the material that could capture a person’s essence outside of temporal particularities. They believed that this art form offered “an ideal eternal form of continuation” for the person’s spirit (Maxwell 33). Indeed, the Field’s visit to Mary’s tomb at Westminster Abbey in May of 1890 speaks to inanimate sculpture’s ability to animate the dead. “I saw again Queen Mary’s effigy,” Cooper writes, “the figure lying white before God. Are we doing wrong to the noble brows? I felt shame of our wild, dramatic work” (Binary Star 117). What lies in front of her is a statuesque version of Mary, but the experience makes her attuned to Mary’s disappointment. Mary herself echoes this connection between monuments and essence near the end of the play when, approaching her death, she states:

I have never

Worn mask to God; before Him I could lie

As a white effigy, and let Him probe

Through to my soul. (258)

It is her form as a “white effigy” that allows God to access her soul, her innermost self. Mary stresses a key point about the function of monuments: they should not mask someone’s character but instead facilitate a more complete experience of interaction. The verb “probe” confirms that: the object functions as a means to an affective communion. The “white effigy” style of the book signals to the reader that they might be able to achieve the same result. By crafting a monument-like exterior, the Fields construct a document that encourages readers to begin a similar affective communion with the queen and that offers not objective historical authority but a process of experiencing a subjective, embodied response.

Texts & Sighs: Embodied Memory in History

<16>While the Fields believe in the affective power of objects, including books, The Tragic Mary contends with an overreliance on textual documentation in historical engagement. The Fields’ ideas about affect contrast prevailing attitudes about history. Historical recovery in the nineteenth century was a field dominated by men that prized accuracy. Certainly, the era boasts variations in its approach to history, but among its many manifestations, it is clear that that history emerged “as the guardian discipline of ‘truth’ in the nineteenth century” (Kucich 17). Following the Enlightenment, a new emphasis on documentary research, evidence, and facts in contrast to faith, tradition, or custom carried into the nineteenth century (Jann xvi). The idea of accuracy was intimately connected to records that could be stored and analyzed and led to an emphasis on writing and text as the essential mode for transmitting knowledge (Taylor 16; Schneider 13). Yet, though heralded as a discipline of objectivity, nineteenth-century historical research was beset with the ideological investments of those creating it. The diverse methods of historiography revolved around the attempt to fix material fragments into a unified and teleological account from the present perspective. One of the main characteristics of Victorian historicism across its different schools, as Bevir points out, is that it focused on progress and therefore situated facts into “a developmental narrative that covered the whole of human life, perhaps the natural world, and sometimes even the divine” (2). Such a lofty goal assumes that the writer exists at the apex of progress, that he holds the insight to make these claims, and that the past always signifies some universal truth. It denies the fact that the author exists in a particular body at a particular moment in time beset with its own assumptions and that all knowledge filters through that lens.

<17>The preface to The Tragic Mary explicitly takes to task this predominant method of historicizing and its reliance on the written word. The Fields eviscerate Mary’s male biographer—the Scottish historian, George Buchanan—calling out his “reckless pages of prose” (vi). Buchanan vocally denounced Mary Queen of Scots after the death of Darnley, but the problem with these texts such as his, as the Fields suggest, is that they codify representations, passing definitive portrayals down authoritatively as fact, making his personal outrage the basis of historical fact. Even the title of the drama attempts to thwart the textual concretization of representation. The Fields asked Pater if they could borrow the phrase “tragic Mary” from his biographical introduction to Dante Gabriel Rossetti in the extensive anthology, The English Poets: “Old Scotch history, perhaps beyond any other, is strong in the matter of heroic and vehement hatreds and love, the tragic Mary herself being but the perfect blossom of them” (205, emphasis mine). Yet it is unclear why the Fields would have needed to mine Pater for their title since he endows Mary with the adjectival quality of “tragic” only in passing, and since the Fields’ drama, in which Mary does not die, ends up not being tragic at all. Perhaps they explicitly drew the title from Pater to wrest Mary’s representation from the hands of men—Pater and, by extension, Rossetti. Pater solidifies his representation of Mary through an appeal to Rossetti’s earlier characterization, setting up a string of patriarchal descent. The Fields then upset that masculine genealogy by inserting their interpretation into such representations passed on from male writer to male writer. Perhaps also the Fields chose the title to undermine the authority of text and demonstrate that the tragedy of Mary is the manhandling of her identity.

<18>By enumerating these previous representations, the Fields show the way in which Mary remains buried under individual accounts, which should make her more accessible but in fact obscure her character. The more pages these artists produce about Mary Stuart, the less immediate access we have to her spirit and interiority. Historical writers were interested in figures of exemplary women such as Mary Stuart because if women were meant to be quiet and passive, they needed to “explain and hedge the existence” of the women who broke that mold (Burstein 117). Simply because the Fields list texts that mutilate Mary’s memory does not mean she did not have her defenders. As Jayne Elizabeth Lewis points out, some Victorian historians fondly read Mary as the paradigm of feminine virtue, who by chance was thrust into the political sphere and suffered from the machinations of male politicians (178). Regardless of whether historians sympathized with her or not, it is clear that historians resurrected Mary with a specific agenda and crafted her representation to fit the mold of their ideological positions. Inevitably, accessing Mary means sifting through all of these representations, produced by big personalities and representative of those authors’ identities.

<19>Tragic Mary’s entourage of men desire to pin Mary’s identity and fate to their own aims through written texts, much like nineteenth-century histories. Darnley signs an agreement with the rebel nobles and lords, recording his and their intention to divest Mary of her royal power. In fact, when Darnley begins to waver in his resolve, Morton reminds him of this damning document: “We would instruct you, bid you recognize / Your destiny is welded into ours / By doom, by justice, by this written bond” (11). The earl couches this comment as merely a suggestion (“would,” “instruct,” “bid”), but his gentler language concludes with an appeal to the irrefutable evidence (“written bond”). Bothwell’s own political and personal aims also depend on inscription and documentation. With the Earl of Moray, Mary’s Protestant half-brother whom she foolishly trusts as a friend, Bothwell plans to kill Darnley so that he might claim Mary for his wife. Both men draft a bond to kill Darnley while he recovers from an illness at Kirk-O-Fields and push the nobles to draft another bond supporting Bothwell’s marriage to Mary (254, 191). The men depend on these inscriptions and textual evidence to bring their plots into being, to set the Queen’s future to pen and paper.

<20>However, the play reveals the foolishness of these men’s authority, inscriptions, and interpretations since the written texts never lead to the fate nor the identity that these men plan for the Queen. Darnley’s signature on the mutinous contract does end in Riccio’s death, but it does not lead to Mary’s submission. The Queen, in fact, strips power from her husband, planning an escape from the Protestant factions at Holyrood, taking charge of other state matters without his assistance, and protecting him from the co-conspirators he betrayed. The Queen even evades the future that Bothwell’s written text prepares for her. Mary has little recourse when Bothwell forces her to marry him except through silent protestation. It is this silent protestation, though, that undoes the forced marriage. Instead of openly defying Bothwell, Mary concedes to him too much, strategically performing the role of the dutiful wife, and even when Bothwell urges Mary to sign a statement revoking her Catholicism, Mary dutifully signs (207). It is her embodied performance—her looks, gestures, voice—that undermines the efficacy of document. Her blind obedience unnerves him; he calls her a “spirit in disguise” and at one point exclaims, “She is changed. O fate, / Re-make her into woman once again, / For she is gone from underneath my hand” (238). The pun on “hand” means that Mary is gone from his control and that his control resided in written documents. The efforts to pin Mary through textual force fail to hold her.

<21>Queen Mary repeatedly critiques textual inscription, advocating for a closer union between text and embodied knowledge. Speaking with the Scottish nobles, Mary asserts her political philosophy: “One act / Of daring feeds a scantness in the land / Ten penal judgments cannot” (82). The statement favors embodied action as a highly effective political strategy since syntactically an active verb and an object follows the “act,” but no object and no result follow “judgments.” I do not mean to propose an essentialist argument that aligns the woman with embodiment and men with textual inscription, especially since Mary routinely demonstrates her prowess as both a writer and a reader. “[L]et me read the articles. / Stand off! I will interpret,” she orders Darnley at one point (22). Instead, Mary speaks to the contingency and incompleteness of textual documentation. Rebecca Schneider states that what thinking about the disciplines of history and theater together can teach us is that there are other methods of recording besides text and “not everything about the past can be accessed by the ‘living body,’ just as not everything about the past can be maintained in a material archive or technological record” (60). The living body can record and transmit knowledge as well, and even if it is not in the same way as text, it does not mean it is less powerful or meaningful.

<22>Mary demonstrates the power of the body in transmitting knowledge. In contrast to the men, Mary knows her history, and her future, through an embodied knowledge passed down to her through her ancestors. In a conversation with her secretary, Lethington, Mary recounts how, at a tournament she attended at the age of sixteen, the king heralded her as the future sovereign of England and inscribed on her carriage, “Place for the Queen of England.” Yet attraction toward the written title alone does not convince Mary to take the English throne. Instead, she appeals to corporeal affect as proof of her fitness for this position:

A cry for empire pierces up my heart

As sharp as murdered blood, spilled on the ground,

Presses for retribution. I receive

The sighs I breathe; if I am left alone

I catch across the vaults of ancestry

Reverberating sounds. I do not urge

My claims, a racial importunity

Leaves me no peace until its suit be stayed.

Does there not grow in kings a royal gift,

Tradition of the conscience? (58)

More important than an official title or a written acknowledgement are the “cry” that singes her heart, the “sighs,” the “reverberating sounds,” the “racial importunity” and “the tradition of the conscience,” all of which satisfy her. Her inheritance is a physical truth that possesses her body that cannot be conveyed through mere text. Her stature as royalty exists in her very blood, and, while texts can confirm or deny that identity, she is assured of her right to the English throne.

<23>The plot of the text confirms the importance of embodied knowledge espoused by Mary. The men attempt to create documents and text to access Mary’s royal power, but by them doing so, they prove that Mary’s bloodline, her physical form, has the power that text can never alter. Darnley cannot access the matrimonial crown except through text, and Bothwell cannot claim royal privilege until a text confirms his marriage to the Queen. Mary always has the right to the crown through her body. The Fields construct this play as a union between body and text. In their preface, they assign Mary’s specific representations to the male authors who created them, and they expose their own physical presence in the creation of this text with repeated uses of the personal pronouns “we” and “I.” They demonstrate that the text is not a neutral conveyer of knowledge; the text is contingent on the body interpreting and reconstructing. Additionally, by writing a drama that can be performed and should be performed to be complete, the Fields ensure that we need to reinhabit Mary’s body to know her fully. Thus, we depend upon embodied knowledge in the same way Mary does; we still need and use the text to remember, but embodied performance is its necessary complement.

An Un-Tragic Mary: Theatrical Time in Historical Drama

<24>If we look back on Mary’s speech to Lethington, we notice—apart from the emphasis on embodiment—the way she blends times together. She “receives” her sighs, the very breath in her lungs, from “the vaults of ancestry” and “tradition of the conscience.” The past lives and informs her current reality. If characters like Bothwell bend the past to meet their present desires, like admitting his marriage is void on the grounds of incest in order to marry the queen, then Mary operates in a different fashion. The past can inform and sculpt the present and future—the present does not need to explain or modernize the past. Multiple times intersect and inform one another, and our understanding can happen from looking from the past onto the present and from the present onto the past. Engaging in affective transport and relying on embodiment allows for times to touch. The object of study is no longer removed from us. Thus, in stating the importance of affect and embodiment, two aspects of performance, within the historical text of The Tragic Mary, the Fields also interrupt a linear and teleological progression of time, common in nineteenth-century histories, and rely on theatrical time to demonstrate that the past is living and mutable.

<25>The time of performance operates differently from the time of written narratives. Theatrical time—through its process of rehearsal and replay—repeats, recycles, returns, and reconfigures. As Marvin Carlson argues, theater is deeply invested in the past in that it frequently dramatizes history and reuses theatrical conventions, and, therefore, serves “as a site of memory” (4). The genre of the historical drama in particular exemplifies theater’s immersion in the past. Time in the course of a historical drama operates on two levels of understanding. On the one hand, as Herbert Lindenberger suggests, a historical drama is a closed circuit that drives toward a pre-determined conclusion, which the audience recognizes that it cannot alter (24). On the other hand, Schneider adds that this drama reenacts the past in front of the audience, allowing the two temporal planes of the “then” of the historical character and the “now” of the contemporary audience to “bleed, paradoxically, into a shared moment” (40). Both Lindenberger and Schneider agree that this blurring of time in historical drama speaks to the temporal messiness of historical recovery itself. Lindenberger argues that the restaging of historical dramas emphasizes the way the past continually mutates based on the present’s approach to historical recovery (10), and Schneider remarks that theatrical presentation underlines the fact that even in history, “time is decidedly porous, pockmarked with other times” (7). As such, theatrical presentations encourage a new understanding of history as in process, coming alive to us again in the present and alterable in the future.

<26>The Fields’ play is a historical drama, and a drama concerned with reenacting history, of the kind Lindenberger and Schneider investigate. Like Lindenberger notes, The Tragic Mary moves toward a determined end, but along the way, the drama forefronts the intermingling of times. In the midst of an entourage of men all coercing Mary into the future they each envision for her, there also exists Mary’s women, collectively called the Maries, who hold an intimate knowledge of her from childhood to marriage. They repeatedly recount stories from her life, leading Mary to admit to the women that “Your mouths / Make the past warm that haunts me as a ghost” (149). The past transitions between being a “ghost,” an entity devoid of breath, to being “warm” and alive once more. The Maries achieve this through their extensive knowledge of her history, which allows them to draw parallels between the present and past. On the day of her forced marriage to Bothwell, for instance, Mary Seton recounts to Mary Livingstone what the queen looked like when she went to wake her: “I found her wrapt / In her black widow’s weeds from head to food, / But yet appareled in a sort of joy / That frightened me” (198). Mary is simultaneously mourning the death of her husband and feeling the anticipation of a bride on her wedding day. The times merge in her mind and through this juxtaposition, she anticipates the dismal future for this second marriage.

<27>The Maries’ willingness to juxtapose the past and present, to allow discrete timeframes to touch, mirrors the concept of theatrical time. They have extensive knowledge of Mary, a wealth of memory, and they use this knowledge to read her past and present together in dynamic ways. This dynamic memory that bleeds times together invests the Maries with a sort of power that Mary herself recognizes. Mary brings together her women at the times when she is most sorrowful and relies on this female community to sustain her. She states that the Maries are life-giving to her: “Girls, take care of me, / For if you keep me with you through this day / I shall not die” (93). To say that the Maries will not let her die in a play titled The Tragic Mary is important. It is their creative reinvention of her identity, the consistent reading of her past and present together, that gives Mary this strength and this enduring life.

<28>In addition to merging the past and the present in this way, the play also entertains alternative futures for Mary, upsetting a linear trajectory for her story. The play dramatizes potentiality and an openness to her narrative. Mary, for instance, continually dreams and recounts those dreams, opening another field of play. Also, Mary seems to die in the middle of the text after the murder of Darnley, but she springs back to life within a few verses. Her death appears so certain to her brother that he orders the servants to “make announcement of her death” (87). Mary’s dramatized death allows her to “come back to life.” Before she even reaches the scene of her final execution, Mary has already died and lived again; therefore, the play toys with the idea that, having been resurrected once before, her end might not signify a conclusion for her. Mary also gives birth to a son early on in the play, a child who never appears in the text but who presumably lives. He symbolizes the continuation of Mary’s body, something of hers that continues past her death.

<29>Potentiality is a hallmark of the theater; with each new performance, the text can be remade by new bodies and new visions. These nods to reembodiment of Mary—in a resurrected body, in a child, in a new reality—all call upon the new embodiment that happens each time another performer becomes Mary. As Rebecca Schneider points out, performance puts things back into a spectrum of possibility: “Thus theatre can be called an art of time, and also an art of passage—the passing of one person, thing, or idea into another person, thing, or idea where person, thing, and idea are in play” (63). The act of performing a scripted historical play reopens that narrative to possibility as actors are able to play within the confines of the scripted text, and with so little textual determinism about Mary, the Fields’ drama does allow for a great deal of play from its theatrical creators.

<30>The drama couples the potentiality of Mary’s story with an indeterminacy about her fate and an emphasis on rebirth and reanimation. In her final monologue to her small band of supporters, Mary both reclaims her representation and leaves that representation open-ended and replete with possibilities. Delivered in “a frenzy,” her final monologue recounts the horrors Bothwell forced on her and concludes with the following self-assertion:

I have still myself

To set within myself and crown, the true

Religion to give faith to, a lost love

To weep for through the long captivity

Of unenjoying years, and the whole earth

To gain, when I have repossessed my soul. (260)

Despite the “narrative” end, Mary looks toward the future. The word “when” here underlines that fact: Mary can see to a future point with certainty. The paradoxical repetition of “myself” (“I have still myself / To set within myself”) suggests that Mary sees multiple versions of the “self” and understands the splintering of her identity. The enjambed lines give us a sense of an ending only to be thwarted when we take up the following line. The idea of being still turns into an action—“to set”—in the second line. The finality of a “lost love” signifies a future opportunity “to weep.” The verb “crown” most logically refers to being instated as the next monarch, but it also alludes to the idea of “crowning,” or being reborn. The same ambiguity underlines the word “repossessed,” which can mean both reclaiming from the hands of others and being reanimated. While Mary speaks of potentiality, the play abruptly ends with these final words and no concluding stage directions to indicate whether Mary rushes forward into battle or not; as such, the Fields allow Mary’s fate to be unwritten.

<31>This indeterminate ending nods to the replay aspect of theater. The past might end in the play after a few hours in a given night, but the show repeats another night, and after that run is done, it receives a new one. Without clarifying an end to Mary, the Fields suggest that Mary is without end, which is true in the medium of the theater. Actors and directors take up the script again and again with each new performance, adjusting the interpretation. Mary can and will spring to life again. Within the play, Tracy Davis’s assertion that “[d]rama, as a discursive practice, foregrounds the multiplicity of temporality” rings true in this verse drama as the audience can envision Mary “repossessing” her soul again the next night (142). In this way, the Fields even undermine the authority of their own text which incorrectly labels Mary as tragic, rejecting the idea that this volume is authoritative and calling into question what is really “tragic” about Mary. Such a move also underscores not only what performance can do to history, but an underlying truth about historical recovery itself. At each moment we take up the past, we leave our traces on it. History will “bend and stretch as the powerful living animal that, through you, it is” (Schneider 41). The Fields use the indeterminacy and openness of Mary characteristic of the repetition of theater to acknowledge and celebrate the traces we future audiences will leave on the text we encounter.

<32>Yet again, the Fields do create a book, a seemingly static and definitive history of Mary, but by embedding performance, they critique and expand the possibilities of text. The physical object creates the document by which Mary can transfer from one person to another, from one time to another. However, what a physical document connotes—historical accuracy, timeless truth, definitive answers—is called into question in The Tragic Mary. Mary’s identity is not clear cut, cohesive, or even present on the page for the first act. Her representation can mutate with each new performance, each new vision that touches this text, and the Fields forefront those reimaginations, as even Mary notes at the end of her story, “All will be recollection” (248). Indeed, all does become recollection. The past exists as nothing except what it becomes through us, even for those who assume historical research can achieve accuracy. In creating this hybrid text, where embodiment, affect, and theatrical time are incorporated into the making of history, the Fields remind us that inaccuracy is what characterizes all history. History always touches our time and gets shaped through our hands and our bodies. In leaving space for others’ interpretations, we do not manipulate history to the values of just our present day.

Texts that Live: The Fields’ Collaborative Enterprise

<33>In 1892, Cooper remembers in her journal a conversation between George Meredith, Bradley, and herself about the difference between manuscript pages and printed pages: “We talk of MSS.—I say how much more alive they are than the printed page” (Works and Days 79). Perhaps why Cooper attributes a living quality to manuscript pages is because these hand-written versions carried with them traces of its two writers by not merging those distinctive hands into one creator. Cooper, for instance, describes the Fields’ dramatic writing as explicitly the product of two minds when she writes to Meredith that, “[s]ome of the scenes of our play are like mosaic-work—the mingled, various product of our two brains” (3). A manuscript copy with its distinctive handwritings reflects Cooper and Bradley’s distinct embodied selves. In a printed page, those different voices and selves are lost for the sake of uniformity.

<34>With the Tragic Mary, the Fields expand the possibilities of the printed page by honoring that type of mosaic-work and reflecting the importance of diverse creative energies. Jill Ehnenn argues that the collaborative partnership of the Fields queered the single-genius notion of print culture. The hybrid form of the verse drama has a similar effect. While they write their dramas as printed books, a form that was equated with single authorship, their explicit appeals to its dramatic nature—and its potential for reenactment across time—upset the notion of a sole creator and an authoritative, dead record. Just as their plays illustrate collaboration between their respective creative energies, The Tragic Mary requires the participation of directors, actors, and audiences for its complete realization. In order to access the elusive and unreadable character of Mary, others need to participate in her characterization. Collaboration, not just between Bradley and Cooper but also between the Fields and future readers, is embedded in the document. In this way, the Fields create a work that retains some of that liveness associated with manuscripts.

<35>Creating a living text also has implications for the historical goals of this play. The Tragic Mary is designed as yet another enduring representation of Mary Queen of Scots, but the Fields also undercut its ability to be definitive, complete, and accurate. The drama asks the reader to study (the Fields in fact labeled the work a “dramatic study” in their journal, which implies an active and ongoing practice) and commune with Mary, but not reify her. It encourages a type of memory that honors varying affective encounters. The audience can leave their traces on Mary as much as Mary leaves her traces on them. The Fields were obviously invested in the question of whether authors can do justice to the memory of women since eight other of their plays feature the stories of significant historical women.(4) In The Tragic Mary, the Fields set forth their guidelines for a new method of history that leaves open space for the future to touch, rethink, and breathe life into the past.